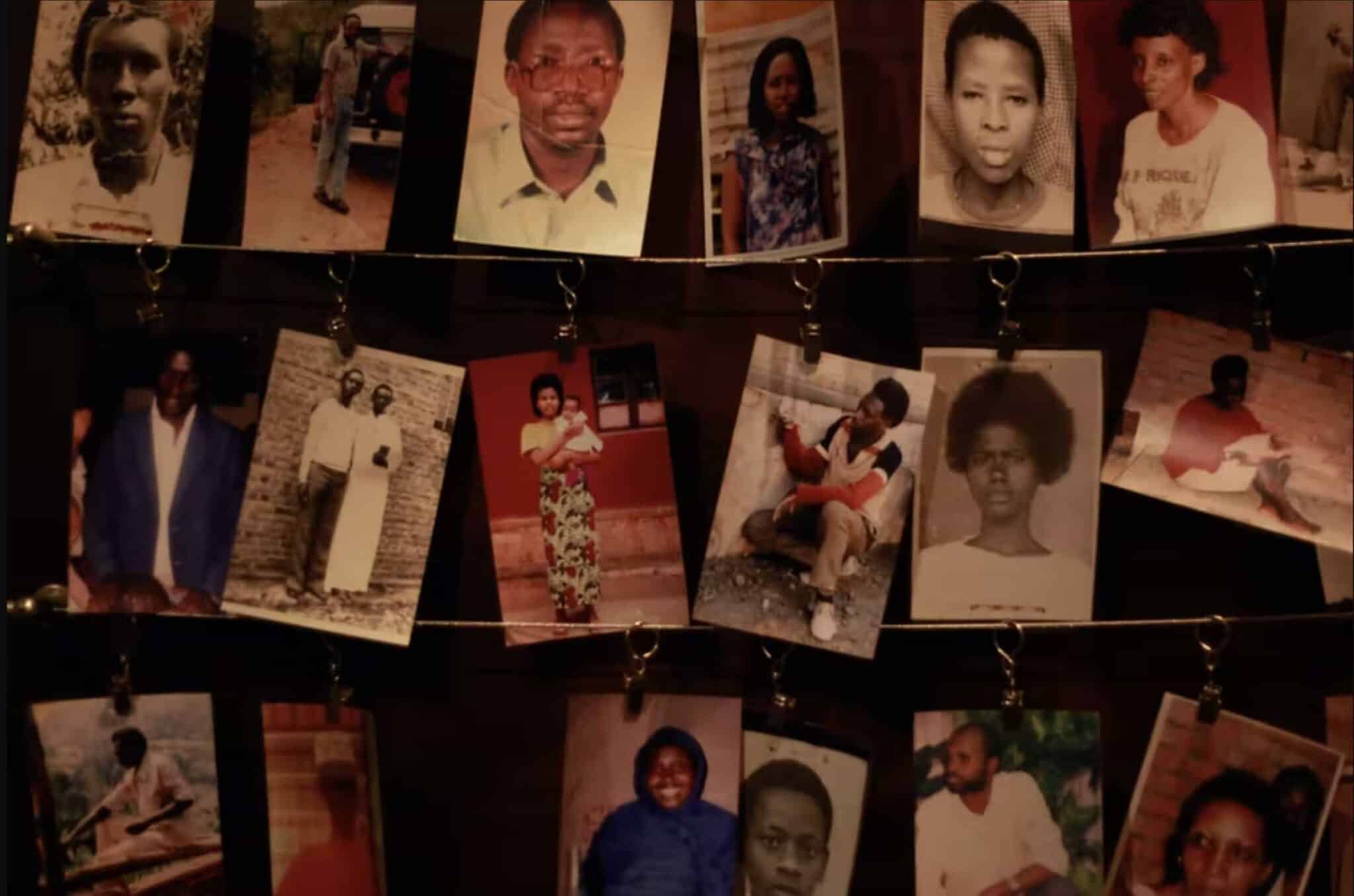

The need for reconciliation among the people of Rwanda was great after the events of the Rwandan Genocide.

Tensions between two of Rwanda’s ethnic groups – the Hutus and the Tutsis – had already been escalating for years. Then, in April of 1994, a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down, killing both men.

Despite there being no evidence, members of the Tutsi ethnic group were blamed. A call to arms went out over the radio from the Hutu-led government. Within hours, Tutsis were being indiscriminately killed by their Hutu neighbors.

Three months later when the violence came to an end, as many as a million people had been murdered. The majority of the Tutsi population had been wiped out. Most of their killers were still roaming free.

The nation now faced the task of rebuilding and healing, even as the possibility of another outbreak of violence loomed over them.

Enter Ervin Staub

Ervin Staub was a guy who knew a thing or two about the work of reconciliation after great violence. A Hungarian Jew, Staub had managed to survive the Holocaust only because his nanny risked her life to hide him in her own home for the duration of the War.

Coming out of that experience, Staub grew up consumed by the questions: Why do people do terrible things to one another? And, is it possible to stop them?

That line of questioning led Staub into a very prestigious career in the field of psychology. He got his PhD at Stanford. He then became a professor at Harvard University. He was invited speak at conferences all around the globe to talk about his research into the causes of genocide and how to prevent it.

In the aftermath of the horrific violence in Rwanda however, Staub came to feel that researching and giving speeches was no longer enough. He decided it was time to put into action the theories he had spent decades developing.

So he got on a plane and went to Rwanda to help make sure that nothing like that ever happened again.

From BBC.com – Dr. Ervin Staub, now Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

A program takes shape

From his research, Staub knew that one of the best barriers to the spread of hate between different groups was close interpersonal relationships. Especially effective were marriages between members of those groups. And so Staub wanted to create a program of some sort that would actively encourage intermarriage between Hutus and Tutsis.

He began to wonder: It was radio messaging from the government that incited the violence that led to the genocide. Was it possible that the reverse could also be true? Could the radio could be used to bring people together?

Staub set to work with a Belgian NGO and a team of Rwandan writers. Together, they developed Musekeweya.

In short, Musekeweya is a radio soap opera about two fictional villages and two star-crossed lovers from rival ethnic groups. While the show was not so on-the-nose as to explicitly name the Hutu and Tutsis, it was written such that each could clearly see themselves in the stories that were being told each week.

The show was an immediate sensation.

In fact, it was so massively popular that when the two main characters were finally set to get married, listeners demanded that the show’s producers hold a live-action wedding in the national stadium so that the whole country could show up to watch!

A Surprising Discovery

But here’s the rub. When a Princeton researcher came to Rwanda a year after the show debuted to study the effect it was having, she unfortunately found that people’s beliefs weren’t shifting much at all.

While they enjoyed the show immensely and followed it’s plots with great interest, they still didn’t believe in intermarriage and they still didn’t believe that it could help prevent future violence in their country.

So much for Staub’s hopes that a radio program could change the hearts and minds of the Rwandan people!

This researcher did however find one area where the program was having a major effect though: the rate of intermarriage between Hutus and Tutsis! After just a year of Musekeweya being on the air, rates of intermarriage between Hutus and Tutsis had measurably, demonstrably increased.

Even though their beliefs hadn’t changed their behavior had.

A Lesson for All of Us

What the story of Musekeweya shows us (and shows us in dramatic fashion!) is a somewhat counterintuitive truth. We often think that our beliefs and emotions guide our behavior. But the exact opposite is true!

Behavior precedes belief; action comes before emotion.

It turns out, if you do something long enough, no matter how you initially feel about it, your heart and mind will eventually catch up and follow suit.

You want to be a more grateful person?

Start saying thank you even for trivial things!

You want to be a more loving person?

Start finding ways to show kindness towards others!

You want to be a more forgiving person?

Start forgiving people right this moment!

Honestly, you might not be feeling it at first. Even as you say “thank you,” you might not be feeling particularly thankful. Even as you say “I forgive you,” you might not feel particularly forgiving. But what the example of Musekeweya shows us is that if you keep after it, your heart and mind will eventually catch up. You will eventually be a more thankful, loving, and forgiving person.

Behavior before belief. If it can work for the people of Rwanda in the work of reconciliation, you better believe it can work for us too!

The story about the creation of Musekeweya originally came from an episode of NPR’s Hidden Brain podcast.